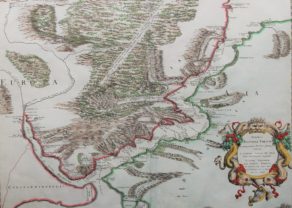

Constantinople (Istanbul)

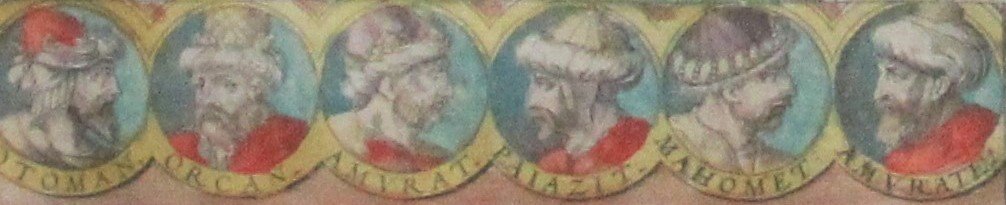

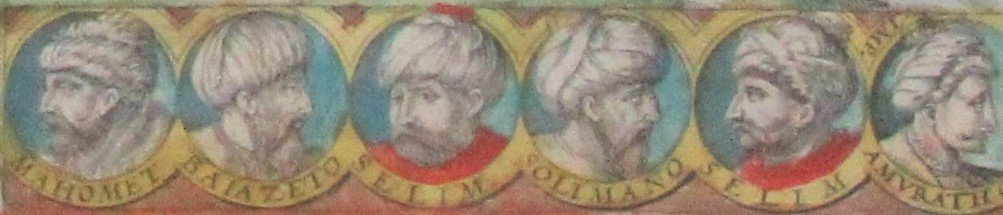

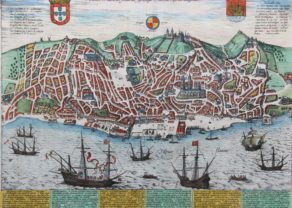

This is the rare second state of the view, with the roundel at the right including the portrait of Sultan Murad III, which is blank in state 1.

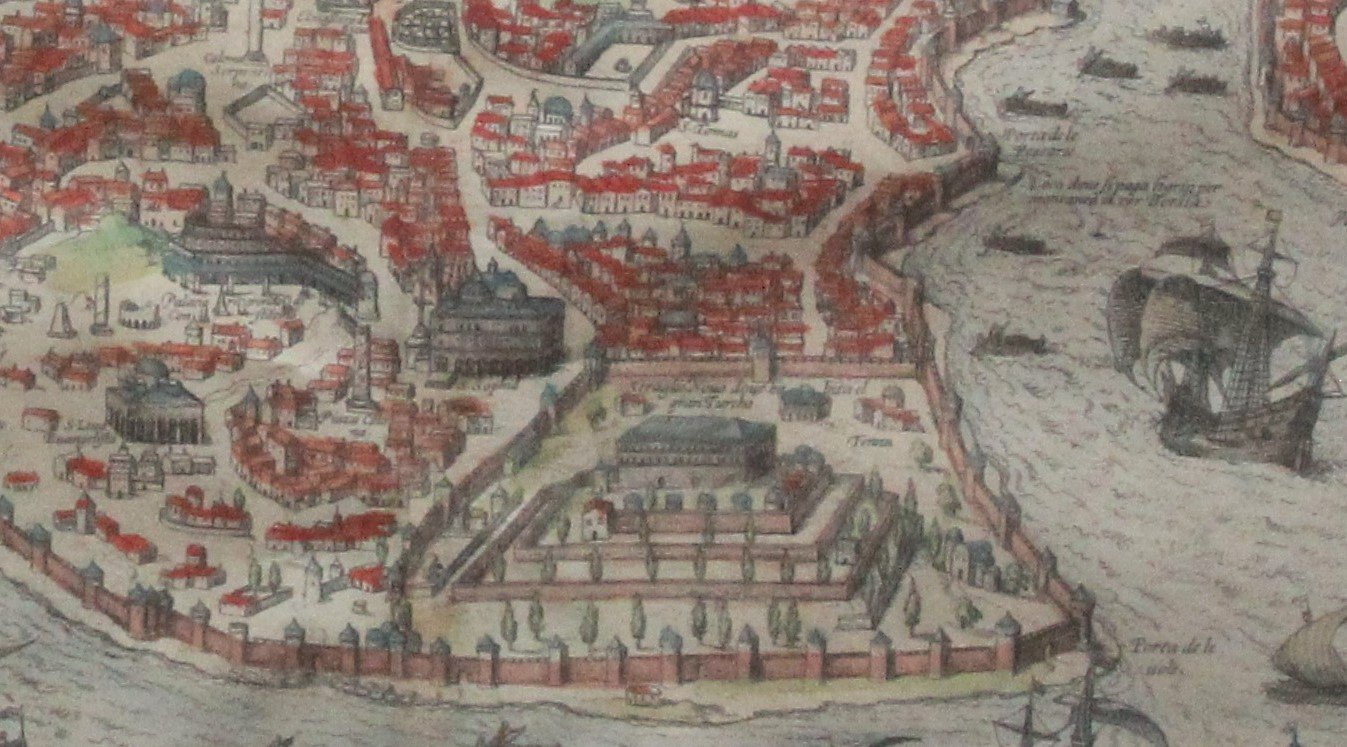

Detail

Date of first edition: 1572

Date of this edition: 1582

Dimensions (not including margins): 33 x 48,2 cm

Dimensions (incuding margins): 38,4 x 51,9 cm

Condition: Very good. Nice colouring. Centre fold at back professionally reinforced. Slight general age-toning. Centre fold as published.

Condition rating: A

Verso: text in Latin

Map reference: Van der Krogt IV, 1912, state 2; Fauser 6824; Taschen, Br. Hog., p.119

From Civitates Orbis Terrarum, Liber Primus, Köln, Gottfried von Kempen, 1582. Van der Krogt IV, 41:1.1, page 51.

From: Theatrum Praecipuarum Urbium, Amsterdam, 1657.

In stock

Julian Stargardt explains:

The following is excerpted from the work of Julian M. Stargardt and his essay on the view:

“To many people today it is strange to reflect that Ottoman Turkey’s European borders extended almost to Venice as recently as the late 19th century while its Asian borders extended almost to the Indian Ocean. Braun and Hogenberg’s map “Byzantium Nunc Constantinopolis” may be part of the Habsburg’s propaganda campaign to detach the name “Rome” from the Ottomans. To contemporaries, the name of the city was “Constantinople” as it had been for the previous 1,242 years and was to remain for the next 358 years, until the Turkish Postal Law of 28 March 1930 officially changed the name to Istanbul, itself a vernacular contraction derived from the Greek “eis tin polis” (‘in’ or ‘going to the city’, i.e. “The City”). In 1572 only a few scholars would have recalled that the city had once been called Byzantium.

* * *

The term “Byzantine” for the Roman empire was first used in 1557 by the Habsburg scholar-librarian Hieronymus Wolf based in Augsburg, the imperial capital of the Holy Roman Empire. Wolf was sponsored by the powerful Fugger banking family whose close ties to the Habsburg dynasty were legendary and whose library was said to be the best in Europe. Wolf uses the name “Byzantine” to identify the latter Roman Empire in his 1557 Corpus Historiae Byzantinae. It seems likely that Wolf consciously used the term Byzantine as a piece of Habsburg anti-Ottoman propaganda at the height of Habsburg-Ottoman rivalry and at a time when the Ottomans were claiming to be the true heirs of Rome, perhaps as a way of legitimizing and making more attractive their rule over a large and, at the time, increasing part of Central, Southern and Eastern Europe. A scant 10 years earlier the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s ambassadors on behalf of the Holy Roman Empire had been obliged to sign a truce with the Ottomans, the 1547 Truce of Adrianople, in which the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V is identified not as “Holy Roman Emperor” but as “King of Spain”, while the Ottoman Emperor, Suleiman the Magnificent, is identified as ‘Roman Emperor’. Under the terms of the truce, the Habsburgs recognized Ottoman control of Hungary, did homage to the Ottomans as the Habsburg’s overlords in Hungary and paid the Ottomans an annual feudal homage of 30,000 gold ducats for their lands in Hungary. One can almost hear Charles V’s teeth gnashing and grinding at the humiliation. These terms were again formalized in the 1568 Treaty of Adrianople. In some senses, though it may seem surprising today, the Ottomans had as good or better claim to call themselves “Roman” as the Habsburgs. The Ottomans were by inter-marriage descended from Roman imperial dynasties, they had conquered much of the former Roman empire, including in 1453 its capital Constantinople, and had absorbed imperial Roman noble families into their society, they believed themselves, or at least held themselves out, to be Rome’s heirs as they vied with the Habsburgs for control of the Mediterranean basin.

With the coming of the Reformation the contest became more complex as the Ottomans, in sharp contrast to some so-called Christian nations of the time, practiced religious tolerance and gave safe haven to refugees from political and religious persecution, like the Jews from Spain, or Protestants and Orthodox from Bohemia and Hungary, or Catholics from newly Protestant realms. To the Habsburgs, it must have looked like a life-and-death challenge with the Ottoman super-power whose borders stretched from Venice to Persia, threatening to cut Austria off from the sea, and who besieged Vienna itself in 1521. Little wonder then that Habsburg propagandists seized on whatever material they could to undermine Ottoman legitimacy and strived to undermine Ottoman claims to be heirs to Rome and the Roman Empire.”

Original title: Byzantium nunc Constantinopolis

Related items

-

Constantinople (Istanbul) – Constantinopolis

by Seger TilemansPrice (without VAT, possibly to be added): €2 800,00 / $3 108,00 / £2 492,00Unique, rare and large frog’s view

-

Bosphorus – Anaplus Bosphori Tracii

by Guillaume SansonPrice (without VAT, possibly to be added): €1 100,00 / $1 221,00 / £979,00Royal cartography: rare and spectacular

Constantinople

Although the name Istanbul existed already for centuries, the official name of this city remained Constantinople until 1930. Greeks from Megara (west of Athens) founded this place around 660 BC and called it Byzantium. Vespasian (9-79) incorporated the city into the Roman Empire. Constantine the Great renamed it after himself in 324 and made it the capital of the eastern part of the Empire. The Topkapi palace at edge of the Golden Horn (see “hornlike” shape of the peninsula) dominates the scene. This administrative and private residence (including 200 ha of gardens) was erected under sultan Mehmet II (seventh from left) after his capture of the city in 1453.

Just above the palace shines the Hagia Sophia with a blue rooftop. The waterway to the Bosporus runs right under. A complete set of the portraits of all 12 sultans from Osman I (1299-1324) to Murat III (1574-1595) embellish the bottom part of this view. Under Süleyman (third from right) I the city achieved a cultural and political climax.